Content Note: Sexual violence, gender-based discrimination

Transcript from Making Joyce Studies Safe for All. Roundtable and open forum organized by the James Joyce Society (September 15, 2023)

Celia Marshik: What kinds of damages are produced by the ongoing problems of sexual harassment that have been described here? What are some of the losses? What are some of the diminishments? What are some of the ways in which Joyce Studies has been shaped by these patterns of harassment?

Casey Lawrence: Many young women, especially students, are leaving Joyce Studies due to issues they have had early on, and we then lose their voices before they’ve even had a chance to contribute. Some of this exodus has been more public, as with Laura Gibbs’s wonderful tweet, but I know some who have just quietly changed fields or left academia altogether. We are poorer for it. That itself perpetuates the problem: if women are the ones who are primarily leaving, Joyce Studies continues to have a gender imbalance.

Katherine Ebury: There is a lack of trust in the field, and that affects opportunities to collaborate with each other and produce good work collectively. I would also like to add that there is a lot of emotional labour for the people committing to improve Joyce Studies.

Zoë Henry: As a community, we become intellectually impoverished, not just by losing these younger female scholars, but also just by virtue of the fact that contributing new ideas is hard when you don’t feel physically or intellectually safe.

Sam Slote: This lack of respect and academic bullying happen in the inherently hierarchized environment of academia. This is exacerbated by declining job prospects, which make these tensions all the more stark and can be emotionally draining.

CM: Is there something intrinsic to Joyce Studies that contributes to making these ongoing patterns of behavior? I am thinking here of Sam’s comment on the sexually explicit nature of Joyce’s work as well as the hierarchical nature of academia. Are there other factors that make this an issue for this particular field??

CL: The culture around alcohol consumption might create some challenges; there are sober scholars who feel excluded because many of our socializing opportunities take place in bars and pubs. Because alcohol is a social lubricant, people can be emboldened to act inappropriately.

KE: This can be a positive in another manner, but the culture of Joyce Studies is quite informal. It is an honor to be elected to the Board of Trustees, but there is a lack of formal procedures that would support us doing things differently. We could be more democratic and have procedures in place.

ZH: I would like to return to what Sam said about Joyce’s explicitness as a writer: it makes me feel sad that we, a community of adults, cannot have conversations about sex and sexuality without crossing into sexual harassment and sexual assault. We need to think seriously about what our responsibilities to each other and to the texts are.

CM: I am reflecting on the overlap between the professional and the personal at conferences. We might feel that we are being open and inviting by going to the pub and having informal discussions, but that doesn’t erase the real power differences of the people there and how that might make issues worse. Are there ways in which the structure of Joyce Studies discredits or ignores this problem? Many of you refer to the Open Letter and the comparative lack of change since its circulation. What is it about Joyce Studies that makes this a difficult problem to address?

SS: The immediate reception of the letter itself became part of the discourse around it: the [James Joyce] Quarterly refused to publish the Open Letter, with a problematic justification, and showed a resistance to hearing about the problem. I thought the letter was remarkably clear, well-written, with clear anger behind it that was nonetheless restrained to outline lucid goals. Yet, it was dismissed, and met with scorn, by scholars in prominent positions. Not wanting to listen, or hear about the problem, exacerbates the toxicity of the atmosphere.

KE: I think the natural home for the publication of the Open Letter, and the aspiration of the signatories, would have been the James Joyce Quarterly, as it is the journal of record in our field. Instead, senior scholars rejected the publication of the letter and the labour of dealing with the issue fell on some brave graduate students at The Modernist Review. That embarrasses me.

CM: Is there something about the decentralized nature of Joyce Studies that contributes to the problem? Do we just expect that someone else will deal with it?

SS: It is hard to say, because the International James Joyce Foundation has limited power; it runs the biennial symposium and that is it. It can set an example around moral leadership by setting example policies for conferences. That might trickle down and be imitated by other relevant entities that organize regular events, like the Dublin summer school and the Zurich workshop, but there isn’t really a headquarters. In many other circumstances, this is a very good thing, but in this one area, it is problematic.

ZH: My experience of Joyce studies has been decentralized, and that hasn’t always been a bad thing. I met Casey at a Finnegans Wake reading group, which was my introduction to this community of younger, junior scholars whose work may not rise to the Joyce Foundation, but that is nonetheless my community. We should recognize that Joyce Studies, though decentralized, includes a lot of grassroots work by younger, marginalized scholars that has not been given sufficient attention in a public forum.

CM: What traditions in Joyce Studies should or might defend against the toxic culture we’ve talked about here? What aspects of Joyce Studies might lend themselves to a change of course going forward?

KE: The Joyce community is an inclusive community; the symposium is inclusive in that anyone who puts in for it will be included in some way. It will include creative artists and people doing all kinds of papers. I see a lot of congeniality, kindness, and good humour across the field. I would also like to point to the women’s caucus, which has been revived, and can regularly intervene in these matters.

CM: How can we better support the complaint process or encourage people to make use of the reporting structures that we do have?

CL: I am reminded here of someone who said that they didn’t report an incident because it would be career suicide and that speaking out against people in positions of power can get you de facto banned from events that are necessary to take part in for professional advancement or to feel like a member of the Joyce community. We have to protect people who come forward, perhaps through anonymity, but definitely by ensuring there is no blowback or negative consequences.

ZH: This fear of career suicide is amplified in a moment when there are so few jobs in the field. Also, students are viewed as sort of ephemeral, as they might not have the same academic security as more cemented scholars, but that doesn’t mean that we are not producing meaningful work that would advance the field. These two problems are interconnected.

SS: Something that has not yet been mentioned is how the Open Letter evolved out of the broader #MeToo movement. If you look at the trajectory of that movement, it seems to now be in a counterwave — almost as if it were the revenge of the abusers. That ugly aspect is finding its mirror in our particular corner of the world as well.

KE: I would like to return to Sam’s earlier point about the need for an ombudsperson, which would reduce the fear of reprisal and retaliation. We need someone in the Joyce field, more than one person perhaps, to receive complaints..

CM: You might want to have more than one ombudsperson, because it might make someone feel more comfortable coming forward. What would conservative solutions to what we are discussing today look like? What might radical solutions look like?

CL: Some kind of strike system: depending on the severity of what is being accused, the first strike might evoke a warning, the second, some sort of consequence, and then three strikes, you’re out. This might look like people being asked not to attend conferences or be keynote speakers. People need to be told “you’re not welcome in this space anymore,” if they continue their behaviour after being warned.

ZH: The optics of having somebody who, amongst the younger female scholars, is acknowledged as a problematic figure remain in a position of power is harrowing.

KE: A conservative solution, that might be radical because it requires a lot of labour, would be for every mentor, every advisor, to be fully engaged in keeping students safe. It should be seen as a part of their academic duty to the student and would require a change of culture in mentorship.

SS: I have a radical idea: start from scratch. Implement an entirely independent conference system that is not run by the Joyce Foundation.

KE: I also had “start from scratch” on my list, not necessarily to undermine the Joyce Foundation, but a new society could fit well alongside the existing structures we have.

SS: It is perhaps not practical, but we could consider a consent workshop, like what is held for incoming college students.

CL: This might also be very radical, but, in the tradition of HR, there could be relationship reporting. If someone is willingly entering into a relationship with someone else in the community they would declare it, which might prevent these things quietly happening. But Joyce Studies is not a company with an HR department, so this would be challenging to implement.

CM: Before opening up the discussion, do any panellists have questions for each other?

CL: I have just recently finished my PhD, so I am not in a position of power; yet, since my blog post and other things that have put me in the public sphere, I have had people report incidents to me. There’s not much that I can personally do other than listen. I am wondering if, Sam or Katherine, who may have also experienced this, you have advice about what we should do if someone discloses something to us?

KE: My experience is similar to yours, even though there is a power difference between us. One of the particular challenges is deciding what to do with a story that the person doesn’t feel safe to report. You can’t forcefully persuade someone to make a disclosure; that is an abuse of power in itself. I try to sit with it and listen, and turn it into action on my part. Often, the person that I am speaking with is not going to stay in the field and I have to accept that.

CL: Should there be a system so that those who have been disclosed to can report on behalf of someone anonymously?

KE: I don’t think it could be done because details would reveal who made the complaint, which would expose them to further risk.

Go to:

Editorial Page

Introduction by Jonathan Goldman and Cathryn Piwinksi

Transcript of the James Joyce Society Welcome Address

Personal Statements by Katherine Ebury, Casey Lawrence, and Sam Slote

Anonymous Open Discussion Transcript

Afterword by Margot Gayle Backus

Sources

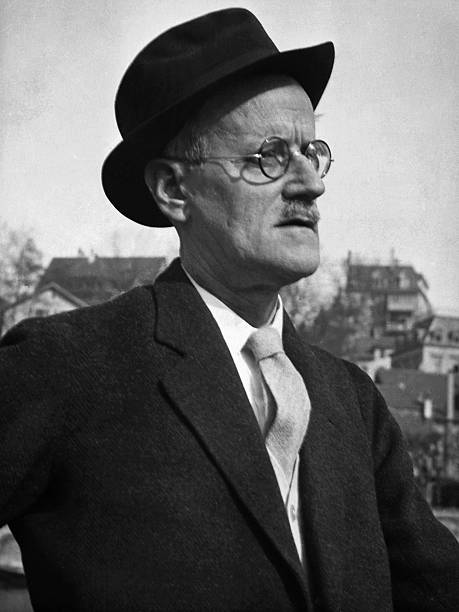

Feature Image Credit: Hulton Deutsch/Getty Images