27 October 2023

Lamia Kabal, Boğaziçi University

Fresh investigations into modernism, with a heightened focus on the experiential and singular production of modernity on a global scale, have prompted a reevaluation of the concept by dissociating it from Western-centric perspectives and associating it with capitalism, generating uncertainties surrounding the category and the boundaries of modernism. Through an exploration of Turkish poet Turgut Uyar’s poetics, which unravel the underlying precariousness and the looming prospect of failure, this essay seeks to contribute to the ongoing discourse on the precarity and uncertainty enveloping the category of modernity and modernism.

Turgut Uyar was among the poets associated with the abrupt transformation in Turkish poetry during the mid-1950s when a group of poets, without a common manifesto, independently published poems characterized by a shared distinct use of language and imagery. Prompted by their radical deviation from established literary trends, critics labeled this new style as the Second New (‘İkinci Yeni’), describing it as ‘abstract’ and ‘meaningless’, while subtly attributing hints of Western influence and even imitation to this unfamiliar mode of poetic expression.[1]

While İkinci Yeni poets’ stylistic deviation may appear to align with the modernist concept of ‘make it new’, and its trademark techniques like fragmentation, discontinuity, and montage characteristic of established Western examples, it was not a derivative approach. Uyar explained that the change in his style was not a collective endeavor of a literary movement aimed at methodically implementing a set of textual techniques but rather an imperative response to the evolving social and cultural dynamics brought about by a capitalist-infused modernity. Uyar’s poetics reveals that the conditions for the possibility of being modern lay in its unceasing reconstruction driven by imminent transformation, which hinges on sustaining the very disintegration that propels it.

After spending years in the provinces due to his military job, Uyar returned to Ankara in the late 1950s, encountering a rapidly urbanizing city marked by the full-swing urbanization projects under the Demokrat Parti (DP) rule, the early years of which marked Turkey’s integration into global capitalism with substantial Marshall Plan aid. Uyar found that neither the Garip (Strange) movement (from 1937 to 1945), once innovative for its focus on everyday language, nor the earlier efforts to unyoke Turkish letters of the young republic from Ottoman legacy by drawing from Anatolian folk tradition could capture the volatile shifts in his environs. The new connotations of modern appliances and constructions, such as ‘the neon lights, big hotels…planes, radios, “penicillin”, 70 story buildings, asphalt roads, automobiles’ needed inclusion in poetry.[2] Rural settings and folkloric motifs in his previous books gave way to a repertoire of unconventional word pairings and images, and a disjointed language effectively capturing urban fragility and a sense of entrapment in the evolving, congested urban landscape, exemplified by terms like ‘blood-cities,’ ‘dead bricks’ (referring to tenements or gecekondu, meaning literally placed overnight, due to increased internal rural-to-urban migrations), ‘night with deer,’ which could not be illuminated by ‘the neon lights and theories,’ and was saved from ‘gladiators and the cogs of wild machines’.

Starting with The Most Beautiful Arabia (1959), Uyar’s pursuit of a new aesthetic is predicated upon the performance of a relentless process of rebuilding. In his article ‘Our Master, the Novice’, Uyar suggests that, following a prescribed trajectory, the artist is ultimately bound to present ‘an ornate, elaborate monument’ to an audience who eagerly observes as ‘each blow of the mallet falls into its place…and exclaim “There it is!”’[3] Hinting that the poet’s unwavering commitment to attaining virtuosity results in a formulaic and immediately recognizable design, Uyar foregrounds the closed quality of such end-product, an ‘elaborate monument’.[4] Juxtaposed against the stagnant, commemorative ‘monument,’ the work of the novice, never finished, is ever new:

You will get a stone and you will start chipping and just when it’s about to take shape, you will throw it away…You will end up with a pile of incomplete sketchy shapes…But as you hug each stone, your strength, your love will be new and fresh. You will work with the pleasure of fear of failure.[5]

Uyar’s preference for incompleteness is closely tied to his conceptualization of poetry, which, intimately entwined with the fabric of everyday experiences, is more of ‘an effort to live’ than an artistic endeavor conceived as a separate, secluded engagement. In a world of flux that resists resolution into an enclosed selfhood, ‘it bears witness to our living’.[6] Hence, at best it should enact a scattered pile of stones, each singular and incomplete, rather than the seamless unity of a monument that is ultimately representative of the past.

Drawing on Werner Hamacher’s characterization of the rise of literary modernity and its strong association with failure as a central concept, Orhan Koçak rethinks Uyar’s exaltation of ‘defeat’ and ‘failure’ by framing them as reflections of the experience of loss as ‘modernity and its literature … emerge from the collapse of traditional orders…and from the loss of the social and aesthetic codes that were once able to secure a certain coherence and continuity for all forms of behavior and production’.[7] Yet, the notion of enacting continuous re-creation of self is rife with paradoxes: the process of re-building selfhood or poetry out of the remnants of the old involves not only relinquishing tradition or breaking secure yet limiting frameworks, but also maintaining the breakdown itself. Celebrating the dynamic process of ‘rebuilding’ with no end-point, Uyar’s poems undertake the sustenance of the very collapse from which the process of ‘rebuilding’ emerges. Only by succeeding to fail and working with the pleasure of failure can the poet bypass a dead end, and stay true to life’s transformative experiences.

The recurring figure of ‘the tightrope walker’, suspended high in the air, encapsulates Uyar’s image of a self invested in crafting poems that perform failure and precarity at the conceptual level. In ‘Poem Explaining the State of the Tightrope Walker on Top of the High Wire’, the tightrope walker humorously relates the precarity of his position:

Your red is red I believe it

Your purple is purple I believe it

Your god is grand, agreed

Your poem is perfect

What is more it has smoke

But what is your name

Please do not disturb my balanceI blend in with all the trees

Crowd or no crowd, who’s counting

Lost in the streets found in my pocket

But the trees are like that

But the streets are like this, who cares

But what is your name

Please do not disturb my balanceMy love might change, so might my truths

By the sparkling wavy sea

Enjoying the water up to my knees

I am smiling at all of you with good intentions

Say whatever you say

I will not fight with you today.[8]

Leaning right and left, the tightrope walker rebels against prescribed formulations for a ‘perfect’ poem, refusing to adhere to them but instead highlighting the lingering potential for impending change. A figure with metapoetic charge, ‘the tightrope walker’ embodies Uyar’s description of creative process: Content with ‘blending in with all the trees,’ he thrives in moments of precarity, where he exhibits profound self-awareness of elusive truth.

Uyar’s figures of precarity and failure not only tell a story of a breakdown, but also proactively anticipate the destabilization of any category. A change so drastic, the Second New necessitated the retroactive naming of the preceding Garip movement as the ‘First New’, implying the inherent instability of modernism’s relationship to notions of newness. Underscoring the socio-cultural precarity specific to Turkey in the 1950s, Uyar’s commitment to ceaseless rebuilding of poetic selfhood mirrors the experience of a ‘self’ that is ‘felt to be on the point of change’ within a singular modernity shaped by the capitalist world-system, as highlighted by Fredric Jameson’s perspective on modernism.[9] In embracing failure, Uyar demonstrates an awareness of the transient nature of the temporal boundaries of modernism and takes on its daunting task, which, according to Paul de Man, entailing constant innovation, exposes the inherent ‘impossibility of being modern’.[10]

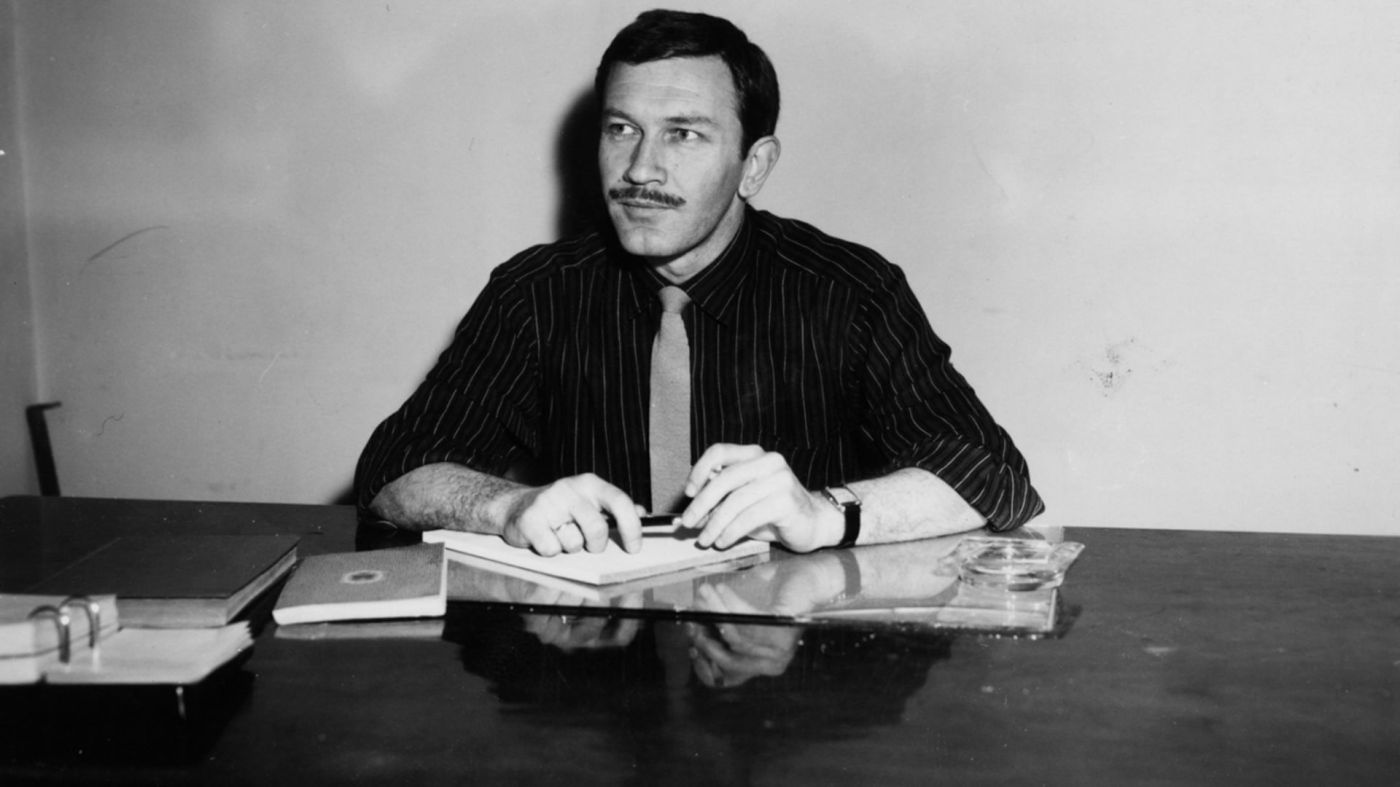

Image credit:

[1] Asım Bezirci, İkinci Yeni olayı [The Second New Incident] (Istanbul: Gözlem

Yayıncılık, 1986), p. 23.

[2] Quoted in Ferit Özgüven, ‘Turgut Uyar: Hangi Soruyu Niye’ in Sonsuz ve Öbürü, ed. by Tomris Uyar and Seyyit Nezir, (Istanbul: Broy Yayınları, 1985), pp. 104, 107.

[3] Turgut Uyar, ‘Efendimiz Acemilik’ in Sonsuz ve Öbürü, p. 156.

[4] Ibid.

[5] 157

[6] Ibid.

[7] Quoted in Orhan Koçak, Bahisleri Yükseltmek: Turgut Uyar’ın Şiirinde Kendini Yaratma Deneyimi (Istanbul: Metis Yayınları, 2011), p. 25

[8] Uyar, Turgut, Büyük saat: Bütün şiirleri [The large clock: Complete poems] (Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2002), p. 121

[9] Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism; or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990), p. 312.

[10] Paul de Man, Blindness and Insight (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), p. 144.

Koçak, Orhan. ‘‘Our Master, the Novice’: On the Catastrophic Births of Modern Turkish Poetry.’ South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 102, issue 2/3, 2003, pp. 567–598.